Patient assessment: Primary survey

Figure 1: K2 FREC 3 students conducting their practical assessments.

What is DRCABCDE?

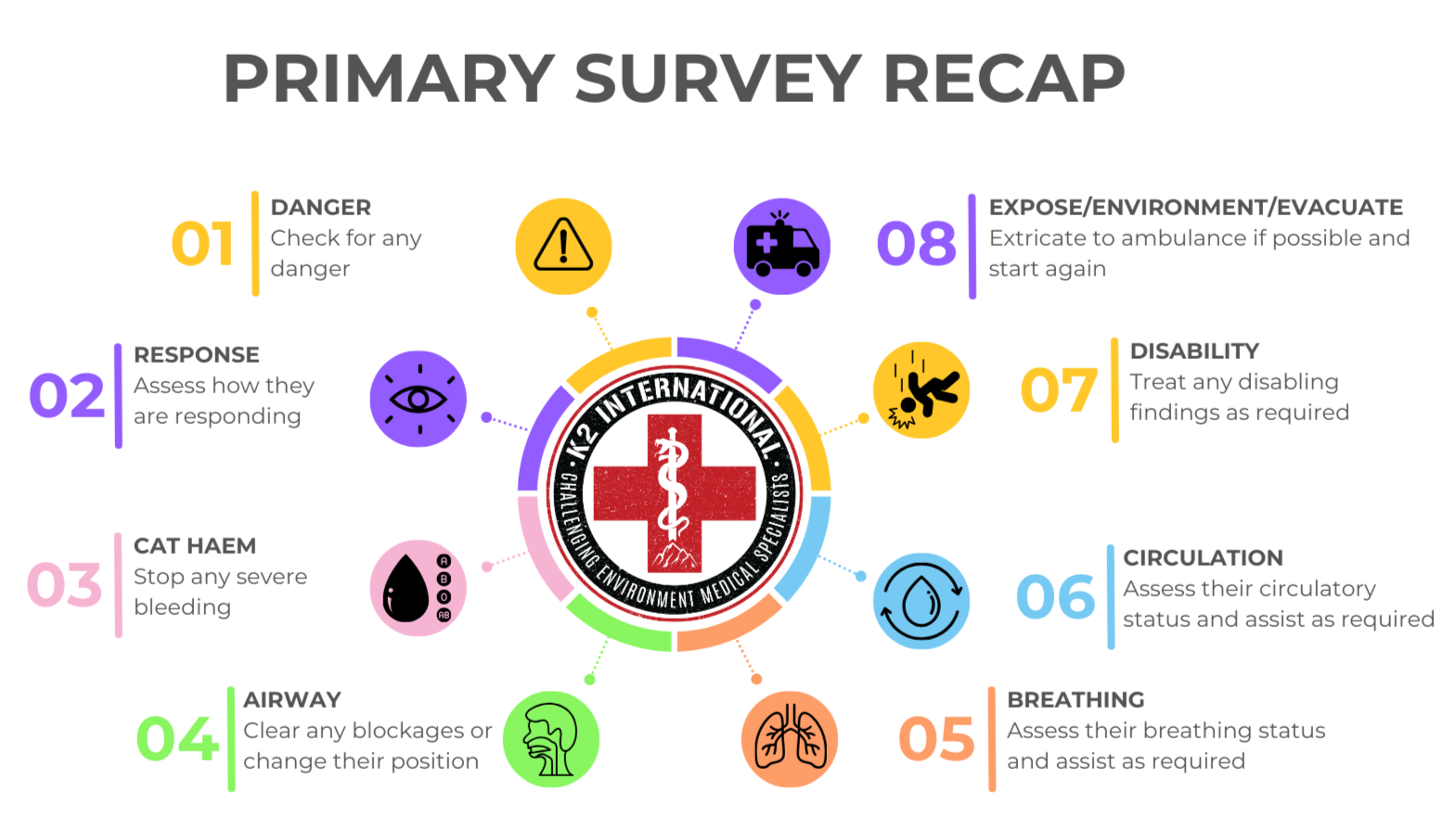

DRCABCDE is a mnemonic used to structure the primary survey, guiding emergency patient assessment and triage by prioritising life-threatening conditions based on a patient’s presentation and symptoms. See figure 2.

DRCABCDE should be used as a practical assessment tool used to help you stay calm and work methodically in any situation.

It guides you through a clear set of checks, starting with immediate dangers and moving through the body systems that fail fastest. This tool allows you to quickly identify and treat anything that is life, limb or sight threatening and is used by first aiders and paramedics across the UK and worldwide.

Think of it as your quick “big sick or little sick” check; a fast way to decide what needs attention right now and what can wait a moment longer.

Figure 2: K2 International Primary Survey Recap.

So why do we use DRCABCDE?

1. It keeps you safe before anything else

The “D” for Danger always comes first. You cannot help anyone if you are injured yourself; taking a moment to check for hazards prevents one casualty becoming two.

Figure 3: K2 Trainee ECA and EMTs conducting vehicle extrication training with support from the Northern Ireland Fire and Rescue Service (NIFRS).

2. It gives you a plan you can rely on under stress

Emergencies are chaotic and emotional; having a structured method keeps you focused. You simply move through the steps in order: Danger; Response; Catastrophic Bleeding; Airway; Breathing; Circulation; Disability; Exposure. No matter how confusing the scene is, you always know what comes next.

3. It follows the order the body needs to stay alive

This is the most important part. DRCABCDE is not just a memory trick; it is built around basic physiology.

Catastrophic bleeding

Catastrophic bleeding comes first because without circulating blood there is no oxygen delivery. A person can lose consciousness and die within minutes if they lose enough blood. Stopping a massive bleed gives the body a chance to survive the next steps. The following signs, symptoms and tools can be used to detect this:

Blood on the floor and 4 more:

Any significant bleeding (pulsating - arterial), or oozing uncontrollably (veinous) from the limbs or junctions (neck, axillae and inguinal areas).

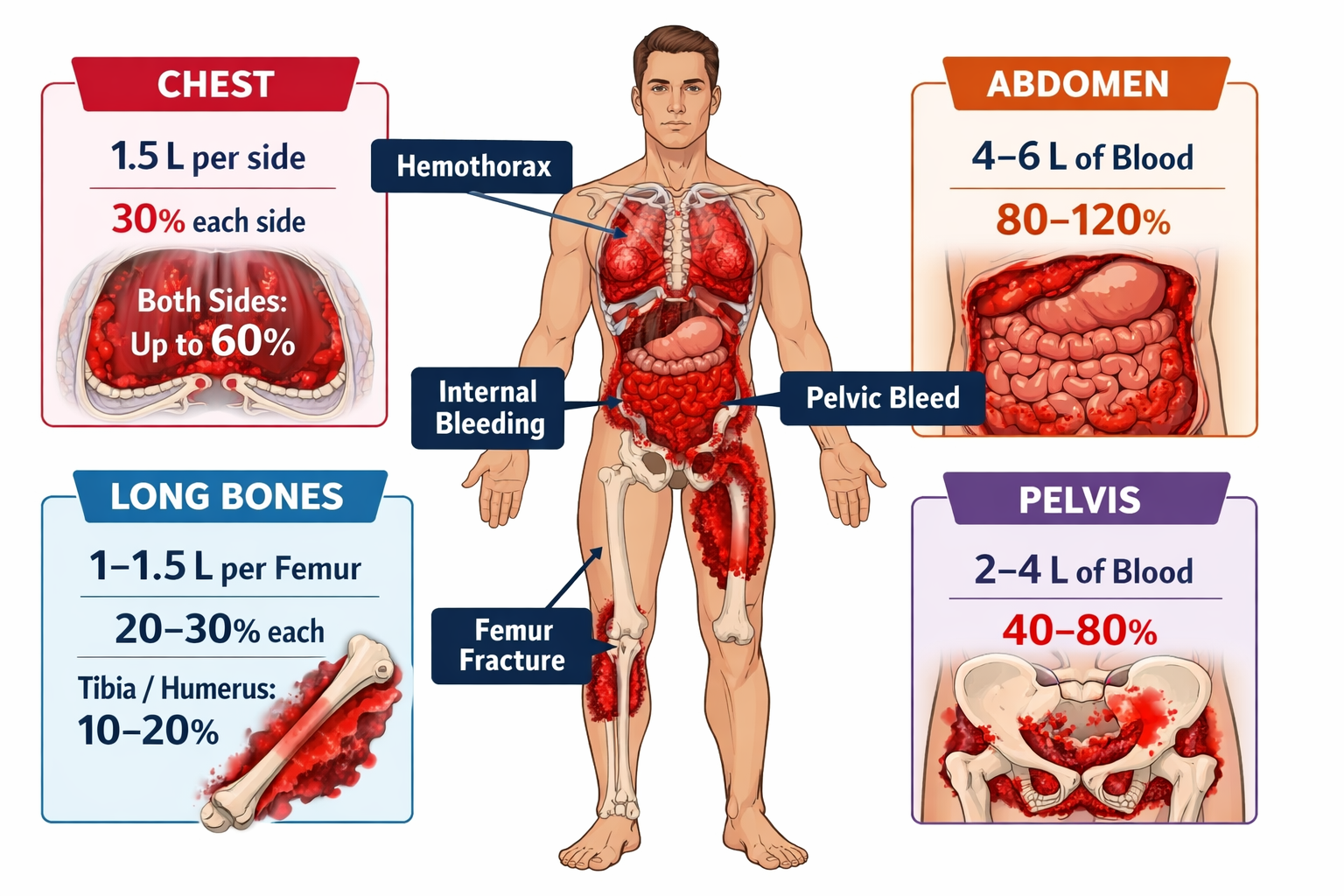

Chest: Penetrating chest wound, reduced rice and fall of the chest. Each lung compartment could potentially hold up to 30% of the average persons blood volume.

Abdomen: Penetrating abdominal wound, distention, guarding, shifting dullness, visible bruising. The abdomen has enough potential space to hold up 100% of the average persons blood volume i.e. exsanguinate them.

Pelvis: Assumed with pelvic fractures (splayed legs) but suspicion can be heightened in men with a priapism, or swollen/bruised scrotum and in anyone with reported urge to urinate with little to no flow. The pelvic girdle is capable of holding up to 80% of the average persons blood volume in extreme scenarios.

Long bones: The femoral area can each hold around 30%, with the the lower legs holding around 20% each. If femur fracture is suspected, latest evidence suggests simple splinting may be as effective as traction splinting although further research is still required.

NB: The stated ranges above are just ranges and meant to illustrate a point. It is highly unlikely any blood loss above ~40% will be observed in a still living patient in the pre-hospital care environment. These percentages are based on volumes which have been observed in these cavities during surgery and are therefore having their blood volume replaced at the same time.

Figure 4: Illustration of the potential spaces for blood loss in the human body and the approximate volumes of blood each can hold.

Airway

Airway comes next because you cannot breathe without a clear, open airway. If the airway is blocked, oxygen cannot reach the lungs regardless of how fast you try to breathe.

Assess the patient for symptoms of airway compromise which might include:

Stridor - a high pitched upper respiratory tract wheeze which may be caused by a partial foreign body obstruction or swelling of the upper airway.

Snoring - a potential sign the patient’s tongue and/or epiglottis are partially occluding the upper airway.

The patient is point to or holding their throat, a significant sign they are choking. See Figure 5 for how to do deal with this.

Once these factors have been addressed, you may consider the use of airway manoeuvres and adjuncts as per your level of training. Each clinical grade and their level of training in terms of manoeuvre and adjunct is listed below (NB: this is a general list based on UK clinical grades):

First aider:

Recovery position;

Postural drainage.

First responder and Ambulance Care Attendant:

All of the above plus:

Oropharyngeal Airway (OPA);

Nasopharyngeal Airway (NPA);

Bag Valve Mask (BVM).

Emergency Care Assistant Emergency Medical Technician

All of the above plus:

Supraglottic Airway (SGA)*;

Paramedic, Specialist Paramedic and non-intensivist Doctor:

All of the above plus:

Endotracheal intubation**;

Needle cricothyrotomy;

Advanced Paramedic (Critical Care) and Intensivist Doctor (PHEM with EM, ICM or AM CCT):

All of the above plus:

Surgical cricothyrotomy***.

*FREC 3 First Responders may be trained and authorised in the use of SGAs if they work for an organisation with appropriate medical oversight and governance.

**Paramedics may only perform this skill in the UK if trained and authorised to do so. It has not been a universal or standard practice to teach this skill on paramedic courses since around 2015 and thus this skill has become a legacy skill for most, and most UK NHS Ambulance trusts only authorise trained paramedics to do this if they can show evidence that they have maintained sufficiency and competency in intubation as supervised by a anaesthetics Doctor. This ultimately means this is now mostly a specialist paramedic skill or higher.

*** There are some settings such as the military or those who work in high-risk, remote, austere and hostile environments whereby junior clinical grades are trained - but not authorised - to undertake surgical cricothyrotomy. This means that whilst trained to do so, they must seek medical oversight before doing so. This can be operationally restricitve however, and this permission is often sought after performing the skill.

Figure 5: Video on how to treat someone who is choking.

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HGBBu4zr8sM&t=2s

Breathing

Breathing follows because the lungs must take in oxygen and remove carbon dioxide; without gas exchange the blood becomes unusable which cannot take place unless the airway is patent. Although it is important to note that this gaseous exchange can be impaired even with a patent airway. This is when we can start to record “signs” of a patient which can directly confirm or deny compromise of a particualr section of the DRCABCDE assessment paradigm.

Signs to gather when assessing for breathing compromise include:

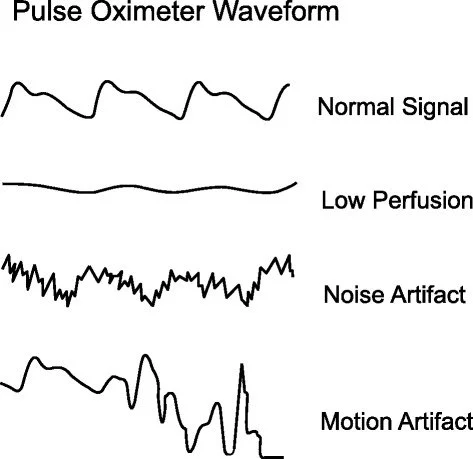

SpO₂: Is it above 94% or between 88% and 92% in those with CO₂ retaining Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases (COPD) such as emphysema and chronic bronchitis. Whilst a good way to confirm or deny a breathing compromise (or respiratory compromise) there are many factors which can cause false hypoxeamia readings (low blood oxygen levels - not to be confused with hypoxia, the set of symptoms caused by a lack of oxygen), such as:

Nail polish on the patient’s fingers;

Inadequate blood flow to the patients fingers. For example Reynaud’s disease or cold exposure;

Blood pressure cuff or tourniquet on the same limb.

A poor SpO₂ waveform is present:

SpO₂ readings should only be trusted if there is a good SpO₂ waveform on the pulse oximeter and/or the monitor. The graphical representation of waveform is known as plethysmography. A good waveform, or ‘pleth’ demonstrates good blood flow in to and out of the area SpO₂ monitoring is being attempted.

Without a good pleth, and therefore good blood flow, theres is no blood and therefore no blood cells for the SpO₂ probe to fire the infrared light at. SpO₂ is determined by firing infrared light into the area where SpO₂ is being monitored from an infrared emitter for an associated infrared sensor to detect. Oxygenated red blood cells absorb infrared light. Therefore a simple equation is all that is needed to determine SpO₂ levels by the device. I.e. if 5% of the light gets through, 95% of the red blood cells are oxygenated.

NB: SpO₂ readings should guide treatment, not indicate it. The above must be considered alongside the patient’s clinical presentation to confirm hypoxeamia before commencing treatment. I.e. a patient who is not cyanosed (blue tinge to the lips), dyspnoeic (short of breath) with a normal respiratory rate with a SpO₂ reading of 68% with a poor pleth likely does not have a breathing compromise.

See figure 6 for what this looks like in different cases.

Good pleth: good entry and exit of blood with nice high peeks.

Respiratory Rate AKA ‘RR’:

Is the rate at which they are breathing (the number of breaths they are taking per minute) normal for them? Normal ranges are as follows:

Most people at rest: 12 to 20 breaths per minute (bpm) depending on the resource you read.

Extremely fit people or people who are acclimatised to high altitudes: Could be significantly lower, down to around 6 bpm. This is because they are much more efficient at exchanging O₂ and CO₂ than most people.

People who are asleep: As oxygen demand decreases at rest, especially during sleep, so does our respiratory rate. RRs as low as 5 are not uncommon for people while they sleep.

CO₂ retraining COPD: Up to 30 bpm for these people can be normal.

If a patient is RR is lower than their expected RR then they are said to be bradypnoeic.

If their RR is higher than expected they are said to be tachypnoeic.

These terms should not be confused with hyperventilation (moving too much air through your lungs) and hypoventilation (not moving enough air through your lungs). Whilst they generally accompany each other, they are different issues. Imagine for example, someone who is taking long, deep breaths in and out, enough so to feel dizzy or light headed. They could have a rate of less than ~12 bpm but they hyper-ventilating themselves.

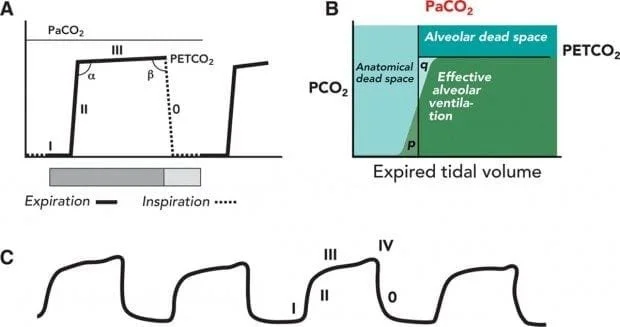

End Tidal CO₂ (EtCO₂): EtCO₂ can only be measured accurately with fairly sophisticated and expensive equipment. But if you are working for an NHS Ambulance Trust or Private Ambulance provider responding to 999 calls, you should have access to a monitor or device capable of capnometry at a minimum (the numerical readout), and ideally capnography (the graphical representation).

Normal ranges: ~4.5 to 6.0 kPa or 35 to 45mmHg depending on the source.

This tool is not only good for observing and confirming different types of breathing compromise, it also allows the clinician to monitor the patient’s respiratory cycle and RR passively and can help confirm airway adjunct placement.

You can read more about EtCO₂, capnometry and caphnography at: https://litfl.com/capnography-waveform-interpretation/

See Figure 7 for a quick visual overview.

Potential symptoms of a breathing compromise:

Cyanosis:

Blue tinge to the lips and potentially other areas with thin skin such as finger tips or nose.

Cyan = blue; Osis = condition - hence cyanosis.

When red blood cells are de-oxygenated they appear slightly blue. At around 92% SpO₂ the 8% of de-oxygenated red blood cells tend to reach the threshold for which blood under thin skin can begin to appear blue. Therefore if a patient is cyanosed, they may have an SpO₂ of <92%.

Tachypnoea:

Simply put, a RR higher than expected for the patient you are assessing (or > at rest for most people).

Dyspnoea:

The medical word for shortness of breath. Dys = difficulty, pnoea = breathing.

This is something the patient can tell you or you can see.

Further assessment can be done to confirm or deny dyspnoea by inspecting for:

The length of sentences the patient can form. Full sentences and stating dyspnoea means mild. Short sentences means moderate. Single words means severe. No speaking is immediately life-threatening.

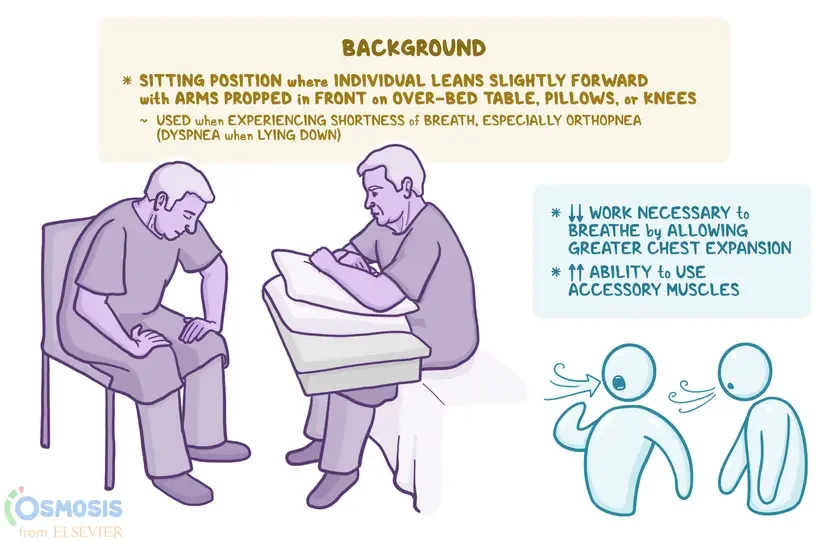

Tripodding: The patient is leant over pushing in their knees and trying to expand their chest cavity. See figure 8.

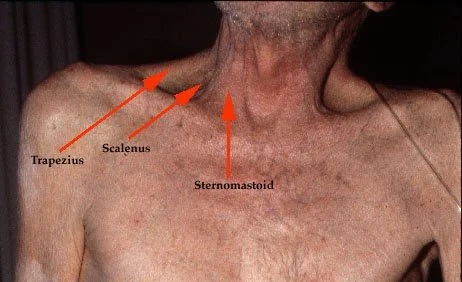

Accessory muscle use: This is the visible use of the muscles of the neck trying to expand the chest cavity further to allow more air entry.

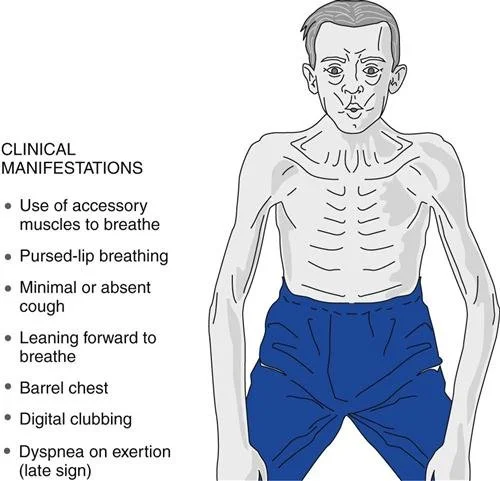

Pursed lip breathing: A sign someone is trying to increase their Peak End Expiratory Pressure (PEEP) to avoid alveoli collapse. Often seen in chronic conditions.

Barrel chest: The changed appearance of the chest to appear more barrel like, similar to a pigeons chest. A sign of chronically entrapped air.

Digital clubbing or fingernail clubbing: Potentially a sign of many things, but is mostly observed in people with metabolic imbalance including chronically raised CO₂.

Hypoxia:

A set of symptoms associated, but not to be confused with hypoxaemia (low SpO₂) as people can be hypoxaemic but not hypoxic - think COPD at rest.

Symptoms can include headache, pins and needles in effected limbs, confusion, irritability, dizziness, and reduced decision making ability.

Signs could include tachypnoea (high respiratory rate) and tachycardia (high pulse rate).

Figure 6: Visual of the different types of SpO₂ waveforms.

Source: https://www.allpcb.com/allelectrohub/reading-pulse-oximeter-traces-and-waveforms

Figure 7: Visual overview of capnography.

Source: https://litfl.com/capnography-waveform-interpretation/

Figure 8: Visual of the tripodding position.

Figure 9: Photograph of an image of a person with COPD who using their neck muscles to help with respiration.

Source: https://www.meddean.luc.edu/lumen/meded/medicine/pulmonar/apd/pp1.htm

Figure 10: A diagram of a person with COPD, likely emphysema.

Source: https://thoracickey.com/troubleshooting-and-problem-solving/

Circulation

Circulation comes after breathing because once oxygen is in the blood, the heart must pump it around the body. A heart that is not circulating blood effectively will quickly lead to symptoms such as dizziness, light-headedness, pale colour, faint and/or collapse and potentially cardiac arrest.

Signs of circulatory compromise could include:

Tachycardia: The medical word for fast heart rate. Tachy = fast rate, cardia = heart. At rest the normal ranges are generally accepted as:

Normal health: 60 to 100 beats per minute (bpm).

Extremely fit individuals: down to 40, sometimes as low as 30 for elite athletes, but not above 100.

Bradycardia: The medical word for a low heart rate. Like tachycardia it is broke up into a prefix and a suffix. With brady = low rate and cardia still meaning heart.

This is used less often to confirm cardiovascular compromise, however the compromise may be caused by the bradycardia leading to hypotension and hypoperfusion, but it may also be a fleeting sign of impending arrest as the heart goes from tachycardia down to zero.

Hypotension: The medical word for low blood pressure. Hypo = not enough, tension = pressure. Likewise this applies to hypertension or high blood pressure, also with hyper meaning too much and tension still meaning pressure. As with bradycardia, hypertension would not be used to confirm or deny cardiovascular compromise. In fact in most cases this is the opposite. However, it can be a fleeting sign of a dissected thoracic aorta which if ruptured, will rapidly lead to haemorrhagic shock.

A good pressure is said to be less than 120/80, or as low as possible without causing the person to faint.

A blood pressure of <90 systolic (the top number, of the BP representing the pressure the heart is exerting on the systemic vessels - the more important of the two in pre-hospital care) is said to be an emergency if associated with the symptoms of shock (listed below). But for some people, this may be normal. For example, young women, people with a low BMI and athletes.

A systolic blood pressure of 180+ with no symptoms is said to be a hypertensive urgency and requires the patient’s BP to be lowered over the next few days, usually by their primary care provider. The same BP with neurological symptoms such as headache or disturbed vision is considered a hypertensive emergency and must have their BP lowered ASAP in an Emergency Department (ED) due to risk of stroke.

Delayed Capillary Refill Time (CRT):

A capillary refill time of over 2 seconds may indicate the early stages of shock and therefore hypoperfusion (hypo = not enough, perfusion = oxygenated blood). While a CRT of >5 all but confirms hypoperfusion and likely shock.

NB: It is important to remember what is ‘normal’ and that these ranges are at rest. A person running a marathon should be expected to have a heart rate (HR) of 150+ thus this does not indicate a medical emergency and an olympian won’t have the same blood pressure (BP) as a 100m sprinter. Therefore ‘common sense’ and a pragmatic approach to patient assessment should be adopted to avoid over referral to different care pathways.

If a patient is showing the above signs of hypoperfusion (low BP, high HR, delayed CRT) AND they are displaying any of the following symptoms, then they are likely to be in the physiological state known as shock. The symptoms of shock are as follows:

Pale colour - due to a lack of circulation under the skin.

Thirst for air ( otherwise unexplained tachypnoea and/or dyspnoea) - due to a lack of blood flow reducing oxygen delivery.

Nausea and vomiting - a paradoxical response by the brain not receiving enough oxygen.

Dizziness/light-headedness - due to a lack of blood flow to the brain.

Confusion - as above.

Reduced urine output - due to reduced or lack of end glomerular filtration (kidney function) which is usually driven by the hydraulic action of blood entering the kidneys above a certain threshold - usually either said to be 90 systolic or Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) of ~65.

Orthostatic hypotension - hypotension when trying to stand up; even more so if hypotensive while lying down.

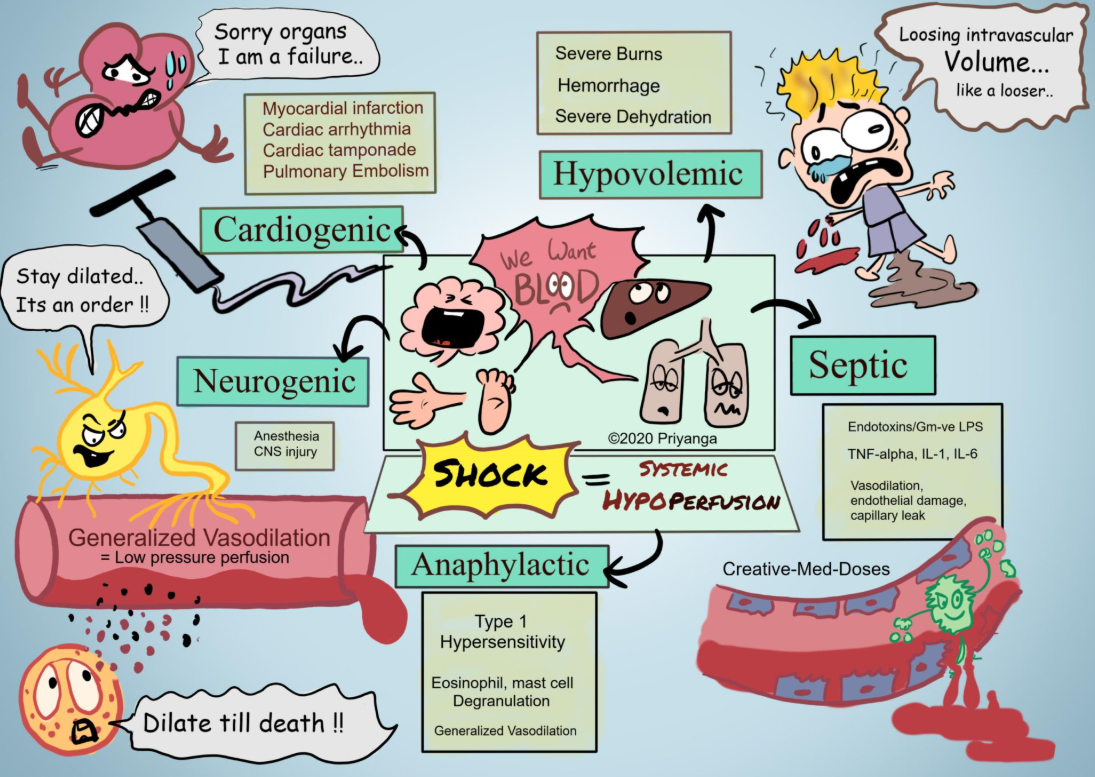

What causes shock?

There are many reasons a person may be in shock. The primary types are listed below:

Hypovolaemic shock: Hypo = not enough, vol = volume, eamic = blood. Hence, not enough blood volume. Caused by two main mechanisms.

Loss of water volume i.e. dehydration secondary to sun stroke, diarrhoea, vomiting etc. Treated via intravenous (IV) fluids and rest.

Loss of blood volume: Also known as haemorrhagic shock. This is loss of whole blood.

Cardiogenic shock: The heart is failing to pump blood around the body effectively enough to meet it’s oxygen demands.

Septic shock: The progression of sepsis that has not been treated or has worsened despite treatment. Causes hypoperfusion via:

Excessive blood vessel dilation;

Multiple organ infection and inflammation preventing blood from entering and perfusing affected organs;

Reduced fluid intake due to sickness and reduced GCS;

Poor kidney function (which plays a role in BP management).

Neurogenic shock: Caused by inappropriate or no central nervous system management of systemic blood vessels leading to widespread vasodilation.

Anaphylactic shock: Widespread hypoperfusion caused by a life-threatening allergic reaction. Caused by:

Systemic over production of histamine by over stimulated mast cells lading to systemic vasodilation particularly around the throat area (angioedema);

Fluids are then also pulled from the blood, intra cellular and extra cellular compartments leading to further hypovolaemia;

Angioedema causes an airway compromise leading to a breathing compromise leading to hypoxaemia and hypoxia of all organs including the heart which further struggles to pump an already limited amount of blood volume.

Treated via adrenaline administration and later, anti-histamine administration.

Neutropenic shock: A form of septic shock observed in individuals who have had their immune system suppressed i.e. recent chemotherapy.

NB: most forms of shock except cardiogenic share similar first aid procedures, lie the patient down to reduce cardiac load and utiliise the blood volume from the legs to perfuse the brain. Do not attempt this in cardiogenic shock - although they are unlikely to let you - as their pulmonary oedema will spread to a larger area if they lie down causing acutely worsened dyspnoea.

Figure 11: Infographic showing the primary types of shock and their causes.

Source: https://creativemeddoses.com/topics-list/shock-systemic-hypoperfusion/

Disability

Disability, whilst less immediately life-threatening than some of the compromises listed above is still a crucial step in your primary survey.

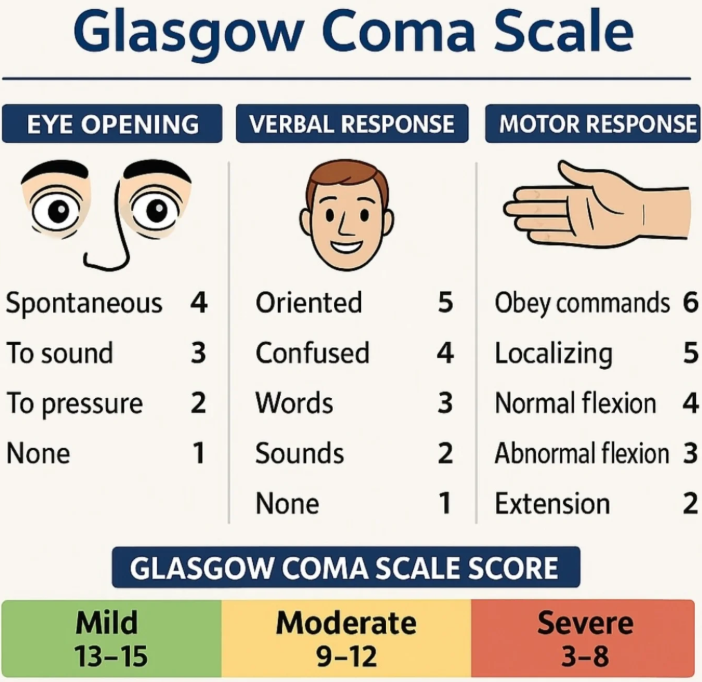

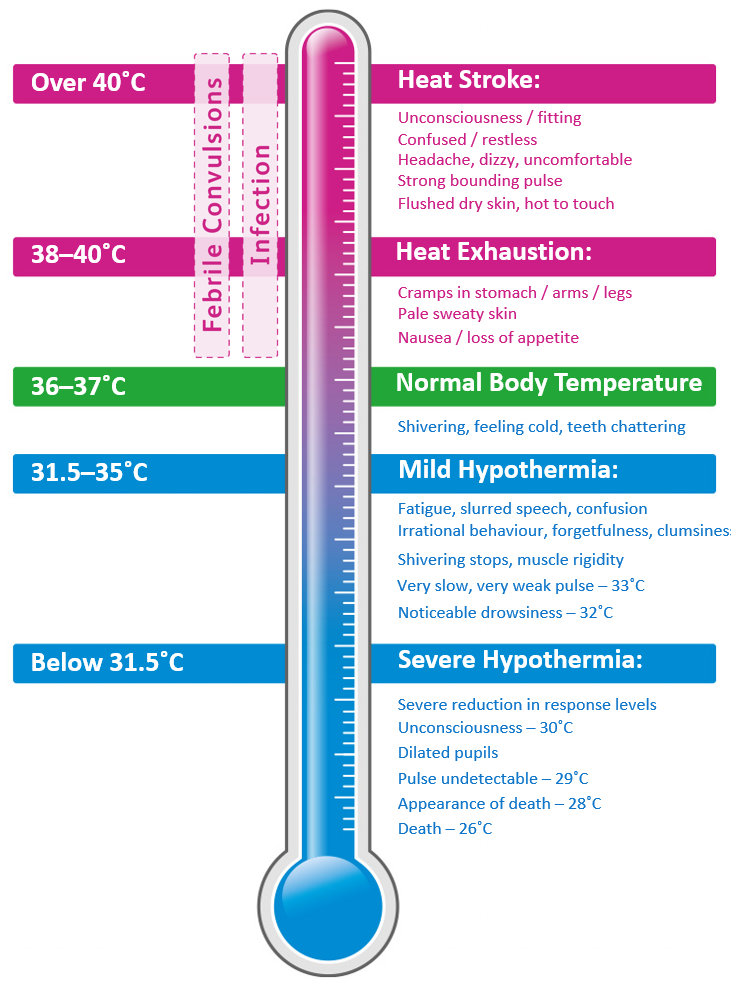

Signs such as the patient’s Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), Blood Glucose Level (BGL), and temperature will be checked and addressed if possible here, but also symptoms and clinical features such as the FAST test for Cerebro-Vascular Events (CVEs) such as strokes and tools such as SLIPDUCT to identify fractures or dislocations which can cause a person to become acutely ‘disabled’ or a chronic disability made worse.

This sequence reflects how quickly each system fails; catastrophic bleeding, airway obstruction and cardiac failure cause death far faster than most other injuries.

Figure 12: Graphic showing how to calculate a patient’s GCS.

Figure 13: Graphic showing NHS BGL targets for diabetic patients.

Source: https://www.nhstayside.scot.nhs.uk/OurServicesA-Z/DiabetesOutThereDOTTayside/PROD_263654/index.htm

Figure 14: Graphic showing normal temperature ranges.

Expose - Environment - Evaluate - Evacuate

Whilst not a part of the immediately life-saving elements of the primary service, E for plays a crucial role in the 3 P’s. Preserve life, Prevent Worsening and Promote Recovery.

But what does each part mean?

Expose: It may be necesarry to expose parts of, if not all of a patient during your primary survey. Think major trauma, if they have a broken femur, they likely have other injuries we need to find and address. But it’s not just for major trauma. Think minor trauma, you may want to expose someone with a wounded hand up to their elbow. This will allow you to assess the joints above and below the injury as well as provide a wider ‘sterile’ field for wound care. Or even medical, think about myocardial infarctions that require a 12-lead ECG. They must be exposed in order to do this correctly. However, we must at all times consider the next point - our environment - and remember we must preserve dignity at all times. Privacy, Ventilation and Lighting (PVL) are key aims. Working on an ambulance? Expedite your assessment if no immediately life-threatening issues were detected during your primary survey and evacuate to your ambulance where PVL is much more likely. In a crowd of people? Have them form a barrier and face the other way.

Environment: Alongside maintaining an environment that promotes PVL and therefore patient dignity, we must also consider how different environments can positively or negatively effect our patients.

Cold environments: In a cold environment and unable to evacuate to a more appropriate place? Protect them from the earth with an insulating layer and layer blankets and foil blankets if possible over them. Crucially, we must remember if the patient is hypothemric they are unlikely to be a soruce of heat themselves. Therefore, a safe source of heat must be in the with them. Perhaps another person? A warm but not boiling hot hot water bottle? A pet? Once moved into a hot ambient environment, remove the foil blankets to allow the ambient heat to get to them. Remember, if their temperature is low - go slow. Warm them up slowly! Prevention is also key, if they don’t get hypothermic in the first place they are easier to assist.

Hot environments: Likewise, if you’re in a hot environment and unable to remove them to somewhere like the back of an ambulance with an AC system? Move them to a shaded area, keep them hydrated to aid with their own internal thermoregulation and prevent hyperthermia in the first instance. If you’re too late, cool them down rapidly! But be careful here, whilst bottled water may be a good way to cool someone down, that water may be better served being preserved for you or the patient to drink and stay hydrated. This means showers, hosepipes or even creeks are preferable to cool people down if available. Ice packs on large veins and arteries such as on the neck, in the armpits or the groin can help too.

Evaluate: Now, we’re at the key stage. We evaluate all our findings. Ambulance personnel are in effect mobile triage staff. We are empowered with the following tasks.

Assessment of patients;

Reassurance of patients and their loved ones;

Diagnosis of symptoms if possible;

Treatment of said symptoms within our scope of practice;

Then once all that is done transport or refer - or as we shall call it - evacuate.

Remember, if a patient’s condition changes or you are unsure what to do - or simply need to make yourself look busy - do your primary survey again.

Evacuate: This is the part of the paradigm that sets pre-hospital staff apart from most other healthcare professionals. Note only do we assess, diagnose and treat (within our scope of practice) but we can also:

Transport: We can transport patients to a range of care pathways including ED, MIU, GP, CCU and more. This is also the part where we align much more with our other emergency service colleagues such as police and fire. Sometimes, only sometimes, we get to drive on blue lights and rescue people from situations they probably didn’t imagine they would ever be in. This is another thing that sets us apart from almost all other healthcare professionals - we have the privilege of seeing our patients in their own environment. The privilege of being called to someone at potentially the lowest point in their life. This factor cannot be understated in it’s importance upon the patient’s care journey and pathways. Sometimes we can notice factors about other inhabitants in the house to, and perhaps we simply get to see what the patient went through in order to need emergency care (think RTC and a wrecked car).

Refer: We can refer our patients onwards onto a limited range of formally agreed alternative care pathways such as the COPD team, or Direct Assessment Unit (DAU), but we can also refer our patients onto a near limitless amount of informal alternative care pathways - if you can find a department or particular physician, clinician or services phone number - you can discuss your patient with them.

4. It works even if you do not know what the cause is

You do not need to diagnose the problem before you treat it; the survey helps you identify what needs immediate action even when the cause is unclear. You do not need to know why someone is not breathing to start CPR; you do not need to know how a bleed happened to stop it. You simply work through the steps.

5. It is the standard used across UK first aid and emergency care

You will find versions of this approach from St John Ambulance; British Red Cross; Qualsafe; and the Resuscitation Council UK. Using the same model improves teamwork and makes handovers clearer.

6. It helps you reassess and stay calm as the situation changes

You do not complete DRCABCDE once and forget about it; you repeat it because casualties can improve or deteriorate quickly. A simple, predictable structure keeps you calm and consistent.

Further Reading

Arps, K., Hernández, A., Miao, E. and LaFayette, K. (2025) Orthopneic position: What it is, uses, and how it helps breathing. Osmosis.org. Available at: https://www.osmosis.org/answers/orthopneic-position

British Red Cross (no date) First aid. Available at: https://www.redcross.org.uk/first-aid (first aid education and structured emergency response resources).

Creative Med Doses (no date) Shock: systemic hypoperfusion. Available at: https://creativemeddoses.com/topics-list/shock-systemic-hypoperfusion/

Loyola University Medical Education Network (no date) Pulmonary advanced physical diagnosis: physiology. Available at: http://www.meddean.luc.edu/lumen/meded/medicine/pulmonar/apd/pp1.htm

National Centre for Biotechnology Information (no date) Trauma primary survey. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430800/ (importance of primary survey in trauma and systematic assessment).

Nickson, C. (2019) Capnography waveform interpretation. Life in the Fast Lane. Available at: https://litfl.com/capnography-waveform-interpretation/ St John Ambulance (no date) Primary survey (DR ABC) demonstration [YouTube video]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HGBBu4zr8sM&t=2s

NHS Tayside (no date) Diabetes and your health: blood glucose. Available at: https://www.nhstayside.scot.nhs.uk/OurServicesA-Z/DiabetesOutThereDOTTayside/PROD_263654/index.htm

Resuscitation Council UK (2015/2024) The ABCDE approach. Available at: https://www.resus.org.uk/print/pdf/node/123 (systematic ABCDE assessment to treat critically ill patients).

September, A. (2025) Reading pulse oximeter traces and waveforms. AllElectroHub. Available at: https://www.allpcb.com/allelectrohub/reading-pulse-oximeter-traces-and-waveforms

St John Ambulance (no date) How to do the primary survey (DR ABC). Available at: https://www.sja.org.uk/get-advice/how-to/how-to-do-the-primary-survey/ (primary survey steps and DR ABC use).

Syed, A., Haag, A. and Mannarino, I. (2025) Exsanguination: What it is, causes, treatment, and more. Osmosis.org. Available at: https://www.osmosis.org/answers/exsanguination

Thoracic Key (no date) Troubleshooting and problem solving. Available at: https://thoracickey.com/troubleshooting-and-problem-solving/

Valente, T. (2017) The how, what and why of EMS pulse oximetry. JEMS. Available at: https://www.jems.com/patient-care/airway-respiratory/the-how-what-and-why-of-ems-pulse-oximetry/

Disclaimer: This guide is provided for educational purposes only. It is not a substitute for certified first aid training. Although we base our information on current UK-approved guidelines (Resuscitation Council UK, St John Ambulance, etc.), performing first aid requires practice, training and judgement. If in doubt, always call emergency services (999 in the UK) and wait for professional responders. K2 International does not accept liability for actions taken by users based on this guide.